Successful programs targeting emerging educational needs can grow from grassroots initiatives to full-fledged institutionally-supported programs but require dedicated groups of educators willing to volunteer their time.

ABSTRACT

Introduction

The Interprofessional Team Training (ITT) Program at Emory’s Woodruff Health Sciences Center (WHSC) began in 2004 to enhance interprofessional teamwork for better patient safety and care. It evolved from small pilot programs to large-scale training sessions involving over 1,500 students from various health professions.

Description of Innovation

The curriculum included TeamSTEPPS® tools and IPEC Core Competencies, with pedagogy emphasizing collaborative learning. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the ITT Leadership Team created the Remote Interprofessional Platform for Learning and Education, a longitudinal, multi-event, remote small-group IPE program.

Results

Despite challenges such as limited funding and logistical hurdles, the ITT Program significantly impacted student training, faculty development, and Emory’s national leadership in IPE. The Program generated scholarship through presentations, research, and publications, aiding other institutions in developing IPE programs.

Conclusion

The ITT Program’s success and IPE strategic planning were factors leading to the establishment of the WHSC Center for IPE and Collaborative Practice (CP) in 2022 and a new IPE program in 2023. The next priority is to strengthen CP through training in simulation, service-learning, and clinical environments across WHSC. Overall, the ITT Program has significantly contributed to integrating IPE into WHSC’s culture and improving interprofessional teamwork and patient care.

INTRODUCTION

When the Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality for Health Care in America released its 2000 report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System (Institute of Medicine, 2000) noting the significant number of deaths caused by medical errors, healthcare institutions nationwide recognized the need to improve patient safety. Faculty at Emory’s Woodruff Health Sciences Center (WHSC) responded to this call and began collaborating to implement interprofessional education (IPE) at Emory, aiming to prepare students to work in interprofessional teams to improve patient safety and quality care.

DESCRIPTION OF INNOVATION

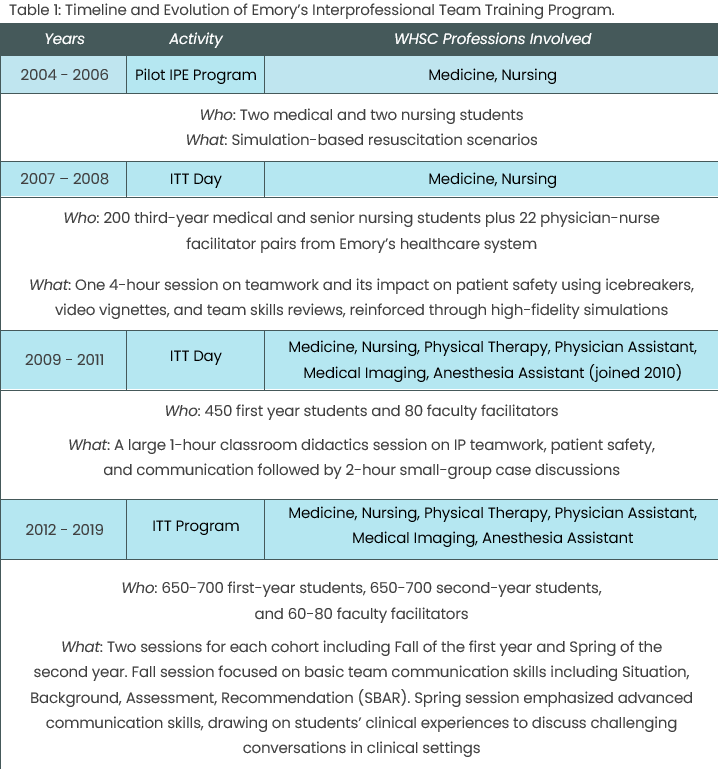

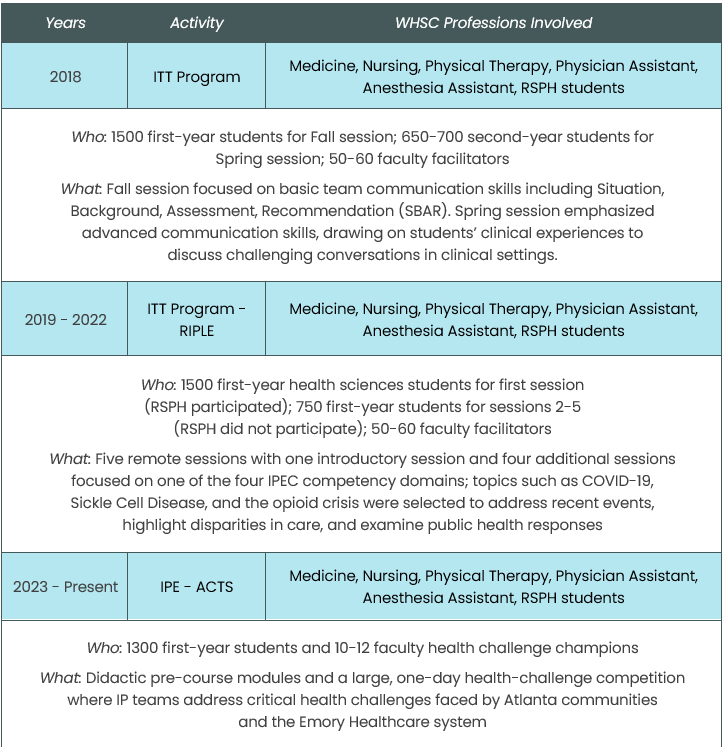

Grassroots efforts starting in 2004 led to small pilot programs with fewer than 10 medical and nursing students. In 2007, the first large-scale Interprofessional Team Training (ITT) Day brought 200 third-year medical and senior nursing students together for a four-hour session on teamwork and patient safety. By 2009, the ITT Program expanded to over 450 students and 80 faculty facilitators from all health professions programs, including medicine, nursing, physical therapy, physician assistant, and medical imaging. Anesthesiologist assistant students joined in 2010. Faculty facilitators, both educators and clinicians, were recruited from WHSC and Emory Healthcare, and an IPE Facilitator Training Program was established to ensure successful IPE.

Between 2012 and 2019, each cohort participated in two ITT sessions: one in the Fall of the first year and another in the Spring of the second year. The first session introduced team training, patient safety, the importance of IPE, and team communication skills. Students learned about the roles in quality healthcare delivery and were trained in Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) structured communication and Check-Back listening skills (TeamSTEPPS, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, n.d.). The second session focused on advanced communication skills, patient advocacy, and conflict resolution (TeamSTEPPS, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, n.d.). Starting in 2018, the Rollins School of Public Health (RSPH) joined the Fall sessions, increasing participation to over 1,500 students from all WHSC programs. Case studies were updated to emphasize interprofessional collaboration, and online modules were introduced on the Canvas platform to prepare students.

In 2020, the ITT Leadership Team responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by creating the “Remote Interprofessional Platform for Learning and Education” (RIPLE). This remote, multi-event IPE program for first-year WHSC health professions students included five sessions. After the introductory session, each subsequent session focused on one of the four Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) competency domains (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2016). By adopting technology and interactive IPE models, WHSC was able to continue IPE despite the challenges of remote learning during the pandemic.

A detailed timeline of the ITT Program structure and the students served can be found in Table 1.

KEY COMPONENTS OF EMORY’S ITT PROGRAM

Leadership Team

The ITT Leadership Team grew over several years, stabilizing with a core group committed to the mission. Representing each program, the team worked year-round to develop the curriculum, determine the format, and complete administrative tasks for ITT events. This dedicated group of IPE leaders drove the development and ongoing refinement of the ITT Program to meet the needs of students, programs, professions, and society. Several members used their work to expand IPE within their programs and create additional interprofessional learning activities at Emory.

Curriculum and Pedagogy

The primary goal of the ITT curriculum was to introduce students to a teamwork culture that enhances patient safety, a vital step in their development as interprofessional healthcare partners. The curriculum incorporated TeamSTEPPS® materials from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Department of Defense, designed to optimize team performance and healthcare delivery (TeamSTEPPS, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, n.d.). The 2011 and 2016 Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) Core Competencies (Interprofessional Education Collaborative, 2011 and 2016) formed the Program’s foundation, integrating the four domains—Values and Ethics, Roles and Responsibilities, Communication, and Teams and Teamwork—throughout the curriculum. Additionally, accreditation requirements and each program’s core competencies and entrustable professional activities shaped the ITT syllabi.

Approaches to IPE pedagogy emphasized collaborative learning experiences designed to prepare students for effective teamwork in clinical practice and continually evolved over 20 years in response to internal and external factors. See Table 1 for the teaching methods used in each iteration. Early versions primarily focused on high-fidelity simulation. As the program grew, the format pivoted to large group didactics addressing the IPEC competencies and structured communication skills followed by case discussions and role-play interactions in small interprofessional student groups led by faculty facilitators from different professions. During the pandemic, the longitudinal IPE format of RIPLE created stable interprofessional student groups to meet with a faculty facilitator four times to discuss the four IPEC competency domains using role play and case reviews.

Internally, feedback from students, facilitators, and the Leadership Team guided changes in formatting and content through an informal Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) quality improvement approach. As more disciplines joined the ITT Program to meet curricular and accreditation needs, cases were continually modified to include a balance of clinical and community health perspectives. Externally, the global pandemic prompted us to create innovative delivery methods. Though remote education is less ideal for teamwork training, RIPLE offered a small-group, longitudinal approach to sustain IPE efforts.

Intentional curriculum design and faculty development were important components of creating and delivering effective IPE pedagogy in the ITT Program. Ultimately, we learned that an IPE curriculum for a large cohort of students and faculty facilitators needs to be flexible, adaptable, and innovative to continuously meet the needs of all stakeholders.

Faculty Development

Faculty development in IPE facilitation was crucial for the ITT Program. Facilitators were trained on patient safety, teamwork, communication, IPEC Core Competencies, and ITT event specifics. Initially conducted as separate in-person sessions before the event, training transitioned to Just-In-Time in-person sessions on the event morning while students attended the large-group lecture. We found that Just-In-Time training proved more effective and efficient, delivering key material immediately before the event and minimizing time off, a common barrier to faculty participation. During the pandemic, faculty training occurred virtually before the initial event with several options to meet schedule differences. Over 200 faculty and staff were trained through the ITT Facilitator Training Program. While not formally measured, the Program successfully introduced many facilitators to structured teamwork training.

Assessment

Student assessment of the ITT Program included pre- and post-surveys for overall satisfaction, the Nebraska Interprofessional Education Attitude Survey (NIPEAS) (Beck-Dallaghan et al., 2016), and written feedback. Facilitators completed post-surveys on their training and the event. The Leadership Team reviewed evaluations to improve engagement and learning outcomes. Students were required to complete the online modules, attend the ITT sessions, and complete the SBAR exercises and reflections. The validated NIPEAS survey added value for program assessment and curriculum adjustments for each discipline.

Scholarship

Program leaders took a scholarly approach to program planning and implementation and have generated 13 publications and 40 presentations, abstracts, and workshops to disseminate their work (Ander et al., 2024; Atallah et al., 2009; Davis et al., 2015; Davis et al., 2019; Davis, Clevenger et al., 2021; Davis, Mitchell et al. 2021; Davis et al., 2023; Geist et al., 2016; Kerry et al., 2019; Kerry et al., 2020; Robertson et al., 2010). They also received a major award for their development of the SBAR Brief Assessment Rubric for Learner Assessment (SBAR-LA), the first validated tool for assessing structured interprofessional communication (Davis, Mitchell et al., 2021).

Funding

The ITT Program at Emory was a grassroots IPE effort with most of the faculty providing in-kind support. Two faculty had roles within their programs (MD and Nursing) that provided some minimal faculty support time for the IPE efforts, not just the ITT Program. The inclusion of the public health students provided additional in-kind support for the development of the online educational modules. Additional support for IPE initiatives was secured through five internal grants, totaling approximately $65,168. However, the growth and implementation of the ITT Program relied on volunteer time by our Leadership Team.

Challenges

The ITT Program faced several challenges that hindered its full implementation and effectiveness. A significant barrier was the lack of institutional funding, limiting resources for Program expansion. Time constraints and the difficulty of aligning academic and clinical calendars among different disciplines created logistical hurdles, making coordinated learning experiences challenging to schedule. Additionally, varying accreditation standards across professions complicated the development of a unified curriculum and assessment framework. The Program also struggled with effectively assessing students’ progress and ability to demonstrate IPEC Competencies, highlighting the need for more structured evaluation tools.

RESULTS

The Program began with a cohort of 20 students from 2 professions and grew to train approximately 1500 students per year across 7 professional programs.

Student Assessment

In the Fall of 2012, student post-ITT survey results (n=200) related to satisfaction and competencies for IP collaborative practice revealed 93% (n=186) indicated they enjoyed working with students from other programs (Davis et al., 2019). Almost all of the students (97.5%, n=195) indicated that knowing how to effectively communicate with individuals in other professions on a team is important, and 71% (n =142) indicated that because of the training, they felt more confident about their ability to work more effectively in a team.

To explore first-year health profession students’ reactions to medical errors and assess any disciplinary differences, ITT faculty researchers analyzed student responses to a video depicting medical errors shown during the ITT event (Davis, Clevenger et al., 2021). Among 373 student responses (80% response rate), 255 expressed emotion-based reactions, with 93.75% of these being negative. Common sentiments included feeling horrified, appalled, and disappointed by the patient’s experience. The responses largely reflected an individualistic perspective on both the causes of and solutions to medical errors. However, no thematic differences emerged across disciplines. The authors highlighted these findings as an opportunity for IPE curricula to incorporate systems-level approaches that emphasize teamwork and patient safety.

In an ITT event designed to teach and evaluate SBAR skills, individual learners were assessed using the SBAR-LA (Davis, Mitchell et al. 2021) on SBAR communication skills before and after the ITT event (Davis et al., 2023). SBAR-LA scores increased for 60% of participants. For skills not demonstrated before the event, the average learner acquired 44% of those skills from the ITT event. Additionally, learners demonstrated statistically significant increases for five of 10 SBAR-LA skills. The evidence indicates the ITT event enhanced students’ skills at communicating patient information in a simulated scenario.

To evaluate RIPLE, faculty researchers administered the NIPEAS to participants both before and after the IPE series (Ander et al., 2024). In two domains, most learners demonstrated increased positivity after the intervention. However, in the “working as a team” domain, no programs showed an increase in positivity, and one program even experienced a decline. These findings suggest that learning together does not always lead to desired outcomes in equal measure. The authors attributed the lack of improvement in teamwork attitudes to limited face-to-face interaction with peers and faculty facilitators, highlighting the challenge of fostering an interprofessional team experience in a virtual setting.

Faculty Assessment

A study of ITT Program facilitator training evaluated changes in facilitators’ self-concept regarding their knowledge, skills, and attitudes toward interprofessional teamwork after training and participation in a team training event (Davis et al., 2015). Using a pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design, 53 facilitators completed surveys assessing interprofessional team self-concept (IPTSC). Results showed significant improvements in facilitators’ perceived knowledge, skills, and attitudes post-training, suggesting that facilitator development programs and involvement in IPE positively impact confidence in teamwork competencies.

IMPACT OF THE ITT PROGRAM

The ITT Program has made a significant impact at Emory University, the WHSC, and beyond, influencing both national and international audiences. Its achievements span several domains. In student development, the Program has trained thousands in team-based healthcare, making it a requirement for all health professions students and embedded in the core curricula for medical and physical therapy programs. Faculty have benefited from team training and IPE opportunities, which have enhanced teaching portfolios and fostered cross-disciplinary collaboration. Institutionally, the Program has positioned Emory as a leader in IPE through scholarly publications, presentations, and workshops, while aiding IPE accreditation compliance for all WHSC programs. Nationally, ITT Program faculty have secured leadership roles in organizations such as the American Interprofessional Health Collaborative, the National Academies of Practice, and the National Interprofessional Education Consortium. Moreover, the Program has contributed to the dissemination of scholarship, assisting other institutions with IPE curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment.

CONTINUED ADVANCEMENT OF IPE AT WHSC

Interprofessional education became part of Emory’s WHSC strategic plan in 2018, and the WHSC Office of IPECP was established in March 2022 providing funding for two directors and administrative support. Building on two decades of ITT Program work, IPE evolved into Interprofessional Education – Achieving Collaborative Team Solutions (IPE-ACTS), developed by leadership from both the Office and ITT Program. Consisting of online modules and an interactive team-based health challenge, IPE-ACTS began in Spring 2024 as a multi-month program for all WHSC students. A modified, one-day interactive interprofessional team-based health challenge occurred on January 31, 2025, where teams collaborated to develop solutions for health challenges occurring in our local communities and health system. Pre- and post-surveys and focus groups were used to assess the program.

DISCUSSION

While IPE is now embedded in WHSC training, the next priority is strengthening collaborative practice (CP). The use of standardized patients and virtual simulations can enhance experiential learning, allowing students to practice interprofessional skills in controlled environments. Additional experiential learning during clinical rotations and service-learning projects can provide real-world opportunities for students to engage in CP. Coordination of various CP activities through the Office of IPECP can provide administrative and financial support to expand CP training in simulation, service-learning, and clinical environments across WHSC. This investment in CP will enable us to fulfill IPEC Core Competencies, meet program accreditation standards, and better equip our students for interprofessional teamwork and patient care.

CONCLUSION

Over 20 years, IPE at WHSC has grown from a small grassroots pilot to a well-organized program aimed at improving the interactions of health professionals for the benefit of public health. The ITT Program trained many students and faculty and established a culture of interprofessional collaboration. Now, through the Office of IPECP and IPE-ACTS, IPE remains a crucial part of health professions training at Emory. Given the rapid changes in healthcare, this program and others like it must stay flexible and adaptable to effectively serve their learners, institutions, and communities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge ITT Program Leadership Team members across WHSC: Douglas S. Ander, MD, FNAP; Cecelia Bellcross, PhD; Sarah Blake, PhD; Carolyn Clevenger, DNP, RN, GNP-BC, AGPCNP-BC, FAANP; Beth P. Davis, DPT, MBA, FNAP; Susan Detrie, Ed.S.; Catherine Dragon, MMSc, PA-C; Laura M.D. Gaydos, PhD; James Kim, MD; Delia Lang, PhD, MPH; Munish Luthra, MD, FCCP; Sally Mitchell, EdD, MMSc; Katherine S. Monroe, MMSc, PhD; Bethany Robertson, DNP, CNM, FNAP; Hugh Stoddard, MEd, PhD; Liz Valdes, MMSC, PA-C; Jeannie Weston, EdD, RN; Administrative Staff from the SOM, SON, and RSPH

The authors received no grant support for this work and declare they have no conflicts of interest in regard to this work.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (n.d.). TeamSTEPPS®: Strategies and tools to enhance performance and patient safety. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/index.html

Ander DS., Davis B, & Stoddard H. Identical Instruction May Lead to Divergent Learning Outcomes: A Comparison of Changes in Learner Attitudes Towards Interprofessional Practice Following an Interprofessional Education Program. Health, Interprofessional Practice and Education. 2024, 6: 2, 1–6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.61406/hipe.317.

Atallah H, Kaplan B, Ander D, Robertson B, Interprofessional Team Training Scenario. MedEdPORTAL; 2009. Available from: https://www.mededportal.org/doi/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.1713.

Beck-Dallaghan, G. L., Abye, T., Herron, S. S., et al. (2016). The Nebraska Interprofessional Education Attitudes Scale: A new instrument for assessing the attitudes of health professions students. Journal of Interprofessional Education & Practice, 4, 33–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2016.05.001

Davis BP, Clevenger CK, Robertson BD, Posnock S, Ander DS. Teaching the teachers: Faculty development in interprofessional education. Applied Nursing Research. 2015 Feb; 28(1): 31-35. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2014.03.003. PMID: 24852452.

Davis BP, Jernigan S, Wise HH. The Integration of TeamSTEPPS® into Interprofessional Education Curricula at Three Academic Health Centers. Journal of Physical Therapy Education. 2019 June: 33(2). doi: 10.1097/JTE.0000000000000087.

Davis BP, Mitchell SA, Weston J, Luthra M, Dragon C, Kim J, Stoddard HA, Ander D. SBAR-LA: SBAR Brief Assessment Rubric for Learner Assessment. MedEdPORTAL. Editor’s Choice Award. 2021 October 18; 17:11184. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11184.

Davis BP, Clevenger C, Dillard R, Moulia D, Ander DS. “Disbelief and Sadness”: First Year Health Profession Students’ Perspectives on Medical Errors. Journal of Patient Safety. 2021 Dec 1; 17(8): e1901-e1905. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000691.

Davis BP, Mitchell SA, Weston J, Luthra M, Dragon C, Kim J, Stoddard HA, Ander D. Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation (SBAR) Education for Healthcare Students: Assessment of a Training Program. MedEdPORTAL. 2023; 19:11293. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11293.

Geist K, Ander DS, White M, Rossi A, Johanson M, Davis BP. Integration of physical therapist’s expertise in the emergency medicine curriculum: an academic model for interprofessional education. Journal of Physical Therapy Education. 2016: 30(4): 17-21. doi: 10.1097/00001416-201630040-00004.

Kerry MJ, Ander DS. Mindfulness fostering of interprofessional simulation training for collaborative practice. BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning. 2019; 5:144-150. doi: 10.1136/bmjstel-2018-000320.

Kerry, Matthew James; Ander, Douglas S.; Davis, Beth P. Interprofessional simulation training’s impact on process and outcome team efficacy beliefs over time. BMJ Simulation and Technology Enhanced Learning. 2020 Apr 20; 6(3):140-147. doi: 10.1136/bmjstel-2018-000390.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. (2000). Building a safer health system (L. T. Kohn, J. M. Corrigan, & M. S. Donaldson, Eds.). Washington, DC: National Academies Press. ISBN-10: 0-309-06837-1.

Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. (2011). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: Report of an expert panel. Washington, D.C.: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

Interprofessional Education Collaborative. (2016). Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: 2016 update. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative.

Robertson B, Atallah H, Kaplan B, Higgins M, Lewitt MJ, Ander DS. The use of simulation and a modified TeamSTEPPS curriculum for medical and nursing student team training. Sim Healthcare 2010; 5:332-337. doi: 10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181f008ad.

Beth P. Davis, PT, DPT, MBA, FNAP

Associate Professor, Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Division of Physical Therapy

bethpdavis@emory.edu

Douglas S. Ander, MD, FNAP

Professor of Emergency Medicine, Director Undergraduate Medical Education, Emergency Medicine, Assistant Dean for Medical Education, Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Emergency Medicine

Published: 5/5/25